Source: Bluberries / Getty Images Signature

Everyone in climate world agrees that more finance is necessary to adapt developing countries to a warming planet. The challenge is scrounging up the requisite dollars, and knowing whose pockets to tap.

A new report out of the Zurich Climate Resilience Alliance (ZCRA) offers a fresh take — and it may not be one adaptation advocates want to hear. It warns that recent efforts to court the private sector may prove disappointing, as even under the most optimistic scenario commercial interests are only likely to deliver around 15% of adaptation needs by 2035 — up from just 3% today. Worse, some private finance could be a poison pill for poor countries, saddling them with payment obligations for decades that slowly erode their fiscal health.

And that’s not all. It further argues that popular ‘blended finance’ transactions — promoted by certain organizations as a way to use public money to scale private investment in adaptation — are pulling in much less commercial capital than hoped. Indeed, the ZCRA’s analysis suggests that as little as 51 cents of private money is being mobilized for every dollar of public funding. Put another way, it would take US$50bn of public money to unlock some US$26bn of private finance through current blended finance mechanisms.

Taken together, the findings threaten to undermine the case that private interests should be recruited to the adaptation finance cause, and could shake up the negotiating calculus of rich and poor nations alike going into the COP30 climate summit this November.

In particular, it could reframe discussions around the ‘Baku to Belém Roadmap’, an agreement struck at last year’s COP to find a way to scale climate finance to at least US$1.3trn a year by 2035.

NEW MATH

Underpinning the ZCRA report’s findings is a distinctive approach to measuring the private sector’s contribution to adaptation.

According to authors Paul Watkiss and Kit England, adaptation specialists at Paul Watkiss Associates, it’s essential to distinguish between ‘financing’ and ‘funding’ to see the full picture. In their framing, the former is the upfront capital provided for an adaptation project. The latter is the stream of payments that repay that capital over time.

Think of it this way: a developing country issues a bond to build a sea wall. Private investors — asset managers, insurers, pension funds — buy in. But it’s the government that services the debt, usually through domestic tax revenues. In this setup, the real financial burden sits squarely on the public sector. The private sector, in the ZCRA report’s view, merely facilitates the deal.

This math suggests that around three-quarters of estimated adaptation funding needs in developing countries are likely to be publicly provided, leaving a rump of 25% that could — in theory — be covered by private entities. But the authors argue that the true potential for commercial investors to weigh in is limited to around 15%, given constraints on private entities and existing levels of public investment. Moreover, most of these funding opportunities are concentrated in agriculture, water supply and efficiency, infrastructure, and cooling — sectors where private capital is likely to make returns.

Realistic Potential For Private Sector Adaptation In Developing Countries*

* For different country groupings under current policy scenarios. LIC = Low-Income Countries, LMIC = Low and Middle-Income Countries, UMIC = Upper-Middle-Income Countries, LDC =Least Developed Countries, SIDS = Small Island Developing States. Note: LDCs include all LICs and some LMICs; SIDS include a mix of income groups. Source: ‘Adaptation finance and the private sector: opportunities and challenges for developing countries’, ZCRA

In addition, to get from the current private sector contribution of 3% — equal to around US$10bn of the US$320bn required annually — to the upper limit of 15% would require a major policy push and far more public financing.

Does this mean climate finance gurus should abandon efforts to raise adaptation dollars from private sources? Not at all, argues Debbie Hillier, head of the ZCRA program at Mercy Corps, one of the alliance’s member groups: “There is clearly scope for the private sector. It’s 15% which is not a lot, but it’s also not nothing — that is US$45-50bn a year,” she says.

In fact, the report’s findings could help focus efforts to engage the private sector, by clarifying where its support can be most effective. “We can’t afford to leave that potential on the table,” says Sabrina Bachrach, an adaptation and resilience finance expert who’s worked with the UN and Atlantic Council.

THE RIGHT BLEND

Some factions in the climate finance debate take a ‘there is no alternative’ attitude to engaging the private sector. After all, public budgets are tight, rich countries are retrenching Official Development Assistance (ODA), and the World Bank and International Monetary Fund — multilateral institutions that have plowed billions into climate — are nervously awaiting the Trump administration’s verdict on whether it will continue supporting them. Without private capital’s involvement, adaptation finance is more likely to shrink than grow.

Experts at the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) say that the public-private approach, pursued via blended finance, is and will continue to be an important mechanism for unlocking private finance. “There's no world in which the answer is that blended capital is not what’s needed,” says Morgan Richmond, a manager at the think tank. “The blended finance approach can help public funds drive private capital if we identify and address the barriers to move innovative financing mechanisms forward.”

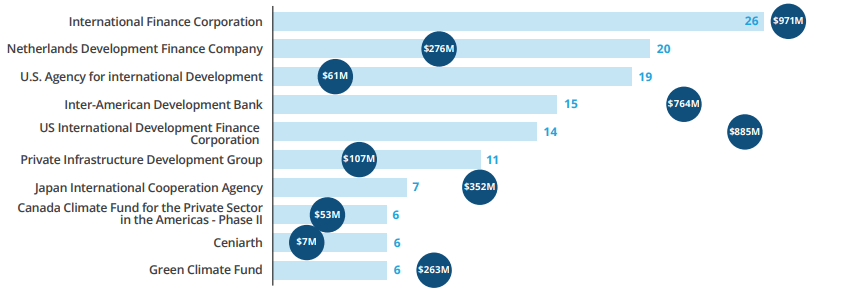

Top Investors By Deal Count In Blended Adaptation Transactions

(2018-2023)

Those in the weeds of blended finance argue the ZCRA’s focus on the low private capital mobilization ratio — just 51 cents of private funding for every public dollar —oversimplifies a more complex picture. Robin Ivory is a manager at Convergence, a global network for blended finance backed by a coalition of public interests. In a conversation with Climate Proof ahead of the report’s publication, she argued that this ratio isn’t the be all and end all. “It’s one metric that’s point-in-time, to kind of give you a sense of where the market’s at, but it doesn’t necessarily, in and of itself, tell the full story,” she said.

Convergence uses a different metric — the leverage ratio — to track the effectiveness of blended finance. This reflects how effective below-market-rate funding is at drawing in market-rate investment. In a 2024 report, Convergence said adaptation deals have an average leverage ratio of 2.12, meaning just over US$2 of market-rate capital is sucked into adaptation for every US$1 of concessional capital. Importantly, the concessional and non-concessional amounts can come from both public and private sources, muddying the waters somewhat on the contributions of the latter.

But in a statement to Climate Proof, Convergence argued that the ZCRA ratio is “depressed” because it includes all public financing — regardless of whether it’s concessional or not — in the denominator, and fails to exclude public finance provided on commercial terms without the intent to mobilize private capital. By their math, the ‘real’ private sector mobilization ratio for adaptation is 1.17, rather than 0.51.

Ivory also said people should consider how mobilization ratios could shift as the market gets more comfortable with climate adaptation as an investment theme. “It’s pretty inevitable that when you have these very nascent and very risky markets, you’re going to require more concessional capital, because … that’s what’s required to bring commercial providers on board.” This is the way with all new technologies and investment themes. Over time, she expects the mobilization ratio to improve as adaptation solutions mature.

Ironically, she sees the current squeeze on public funding as a potential catalyst for innovation and streamlining of blended finance transactions: “We want it to be boring and repetitive and scalable, and at this time when we’re seeing these ODA cuts — and we’re seeing the lack of concessional capital available — now is the time to really show what’s effective and what’s working and how these projects can be scaled up.”

The effectiveness of public finance in closing the adaptation gap may also become clearer with time. “There's a time lag that is hard to capture,” says Pallavi Sherikar, a manager at CPI focused on adaptation and resilience. “Public finance intended to mobilize private investment might be recorded in 2019/2020, but you might not see impacts of private capital mobilization until 2026 or 2027. Figuring out how to track the effectiveness of public finance has to take into account that time lag, which is challenging,” she says.

For her part, Hillier at the ZCRA says the report isn’t out to shame blended finance — it’s there to level-set expectations. “It’s not that it’s a bad idea. It's definitely not that we don’t need it. What we are saying is: be realistic. People talk about [mobilization] ratios of 1:4, or 1:5, or 1:6. and that’s just not the reality,” she says.

MIX AND MATCH

In one area, most climate finance experts agree: some adaptation efforts just don’t work well with private capital. These are the public goods — the big, hairy coastal or river flood protection infrastructure projects — that simply can’t offer private investors returns.

On the flipside, there are a few areas in which it absolutely makes sense to scale the private sector’s involvement. The ZCRA report says that start-up accelerators and financing labs are spinning out innovative private adaptation solutions for the agriculture sector, and to a lesser degree for biodiversity and ecosystems, fisheries, and infrastructure. Most of these projects are targeting Middle-Income Countries rather than the poorest and most vulnerable nations.

Ivory said this tracks with Convergence’s observations. Blended finance transactions have tended to concentrate on agriculture, water management infrastructure, and nature-based solutions, according to the network’s reporting. “Some sectors are more able to generate market solutions, are more able to generate those revenues, and more able to generate market rate returns that could attract commercial capital with the help of a little bit of concessional or catalytic capital,” she explained.

Richmond at the CPI thinks private finance can cast a wider net, though. “There are areas beyond agrifood systems and water where the private sector can finance resilience. There are big opportunities for climate-resilient infrastructure, where we see public investment happening, and increasingly private investment. In some cases, private finance is crowded in by public funds, but in others, there's just an increased understanding of the benefits of investing in climate-resilient infrastructure,” she says.

So could experts be underestimating the private sector’s capacity to close the adaptation finance gap? Venture capital and private equity funds dedicated to adaptation solutions are on the rise. While many are focused on developed, rather than developing, countries, the innovative companies they support could provide goods and services to the world’s poorest and richest alike.

Mazarine Climate is an adaptation fund investing in technologies that address escalating water risks. Its first investment is in New Zealand-based TDRI Solutions — a tech company that helps road owners and operators monitor excess moisture under pavements. This enables them to pinpoint water erosion risks and plan maintenance effectively. On LinkedIn, Mazarine Climate partner John Robinson said TDRI is a “strong example” of how privately financed companies can help vulnerable communities worldwide. Roads are everywhere, after all, and matter as much to poor nations as they do to rich ones.

Source: mikeinlondon / Getty Images

Robinson also says the ZCRA report downplays the role of privately financed solutions — especially tech — in slashing adaptation costs. “Lower-cost interventions allow local governments, NGOs, and even households to deploy adaptation solutions that were previously unaffordable,” he writes.

TURNING THE TABLES

The COP30 summit is barely two months away. A clash between nations over increased adaptation finance is expected, with Brazil’s leaders making plain they want to see greater contributions from public and private investors. It’s possible the ZCRA analysis could reshape the battlelines, and strengthen the hands of those developing country negotiators pushing for larger public finance commitments.

Whether it will convince rich nations to pledge new piles of public money remains to be seen. Some experts are dubious. “I think these publications support the arguments of countries on public finance, but I doubt it will convince developed countries to change their stance,” says Bertha Argueta, Senior Policy and Advocacy Officer at the European Network on Debt and Development.

Indeed, last year’s COP saw progress on a new international climate finance goal only after rich countries were appeased by language saying the money could come “[f]rom a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources.” Therefore, any argument sidelining private finance at this year’s summit is likely to meet a cold reception.

Simon Stiell UN Climate Change Executive Secretary during COP 29. Source: UN Climate Change/Lucia Vasquez-Tumi

Still, Hillier has her fingers crossed that the report will help inform the Baku to Belém Roadmap — by providing clear and credible data on the limits of private finance to fulfil adaptation needs — and catalyze some hard conversations on what a new adaptation finance pledge from developed countries should look like.

A key contribution of the report, she adds, is helping to clarify the often-muddled distinction between ‘funding’ and ‘financing’ — a difference she believes is crucial in global negotiations.

“When we’re talking about the US$300bn of funding to be provided [under the new international climate finance goal], we need to be clear: are we talking about the financing piece, or are we really talk about who’s paying? Having that differentiation much more clear in all of the discussions I think is really important,” she says.

Thanks for reading!

Louie Woodall

Editor